Analyzing suspicious documents, identifying embedded OLE Objects and how they present in various Windows document formats. Extracting embedded object for further analysis. Additional concepts: File signature identification, file extension spoofing, hex editors, common document file structures, file carving (adjacent)

Lab prep:

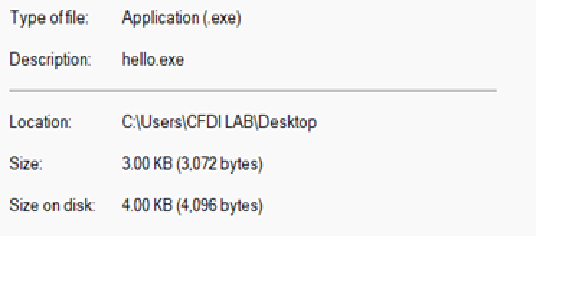

A simple “hello.exe” embedded as an Object into a Word Document. Saved document as “SusDoc.docx”, and “susDoc2,rtf”.

Renamed SusDoc.docx to SusDoc.pdf to demonstrate file extension spoofing.

Tools: Dekstop Microsoft Word (web version will not embed OLE objects), HxD v 2.5.0.0 hex editor, Certutil, 7-zip.

Setting: In this lab, part 1, I’m examining my “SusDoc.pdf”, which is really not a pdf at all. It’s a.docx document, renamed to.pdf to obfuscate the true nature of the document. Note: Never run unknown files on your production system, only in an sandboxed, isolated environment.

1. Opening the “SusDoc.pdf” (default application = MS Edge) results in an error message: “We can’t open this file. Something went wrong”. Something is not right with this “pdf” file. Let’s see if this is really a pdf, because we never trust an extension.

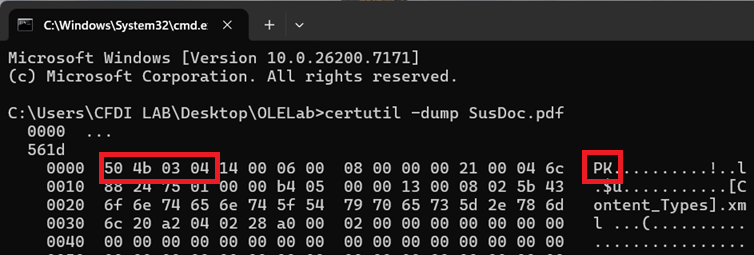

Open cmd.exe > Navigate to your file’s location (or type cmd in the address of the File Explorer from that file’s location)

Type: certutil -dump <filename>

Enter

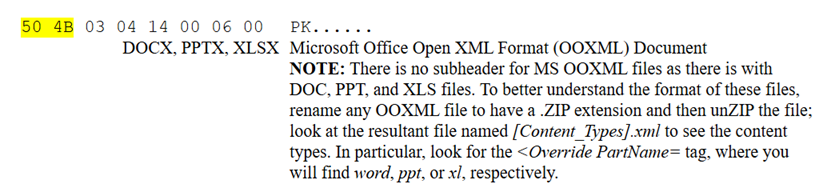

Certutil is a Windows built in utility that you can use for some basic DF quick checks. -dump command displays the raw data of a file in hexadecimal and ASCII formats. This is similar to what you would see in a standard hex editor tool. To verify the true nature of a file, we are looking for the “magic byte” or the file signature. Regardless of what the file’s extension is, the first byte/s will show the actual file type of the file.

To find out what the hex corresponds to, ask Gary: https://www.garykessler.net/library/file_sigs_GCK_latest.html

This is not a .pdf file and that’s why my Edge couldn’t open it. To open this file with the proper application, rename it to the correct extension and open as usual. DOCX files are a collection of xml files zipped into a single file. Renaming it to a .zip will let you see the contents of the file.

Before doing that, I want to look at this file in a hex editor. In my scenario, I suspect that there might be something suspicious inside that file (like an embedded malicious payload). Let’s find my embedded executable.

2. Open HxD > File > Open > select SusDoc.pdf

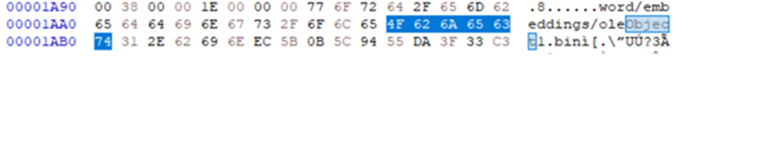

Search > Find > Search by text-string “object”

Found two instances of “object” in my document. There are a lot of various flags you can search for, but since I know what I embedded, so that’s what I used. You can also search for a specific file signature by using the “hex-values” search tab.

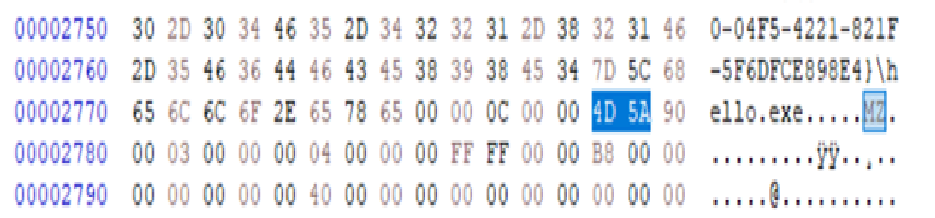

Note: I know that my embedded object is a Windows PE (portable executable) file that starts with bytes: 4D 5A. However, I will not find these values here. The embedded object is compressed and packaged inside the .docx as one of the contents.

However, this is already giving me a number of red flags about the file:

a) the file extension was obfuscated and the file was renamed to something it’s not.

b) there is an embedded object inside. I can’t tell what that object is and it could be benign, but that’s a reason to investigate further.

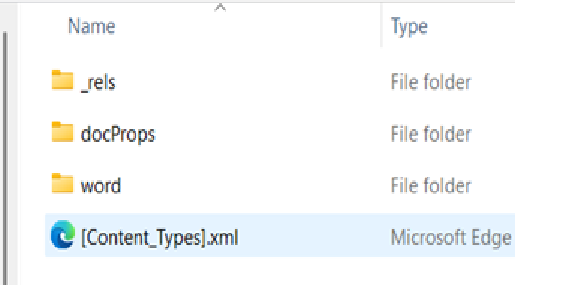

3.) Rename the “SusDoc.pdf” to “SusDoc.zip” and open the archive.

As stated earlier, a docx file is a container of a bunch of other files. Each of those folders could be very useful when you’re looking for clues about the document itself.

_rels: is a map of how all the different parts relate to one another, where the locations are. That’s your reference table for the entire document.

docProps: show the document’s properties, like application version, author, create and modified time stamps, etc.

word: holds the content of the file, including my embedded object.

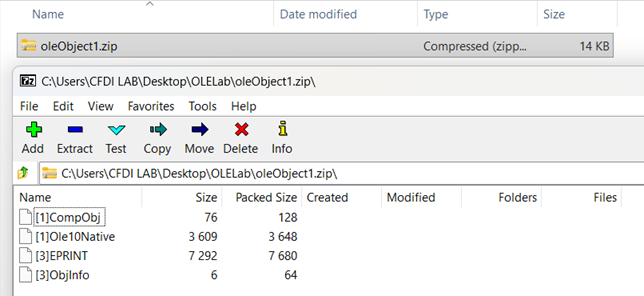

Open “word” folder> “embeddings”> Single .bin file named oleObject1.bin (I only embedded 1 Object. This tracks. Except, what didn’t track was the size. My original “payload” is only 3 KB.

This object is 5 KB compressed from 15 KB! Now, I know my hello.exe is in there, but what’s the bloat all about?? Let’s look inside this file.

4) Extract oleObject1.bin

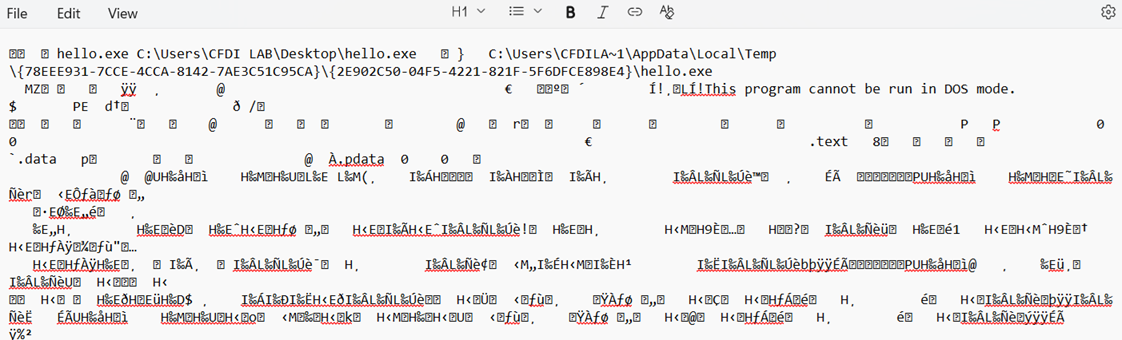

Open the file in Notepad. Note: Turn off Copilot in settings prior to opening. Do not use Notepad+.

A lot of noise surrounding my original .exe. Interesting to note that Notepad is showing two locations:

C:\Users\CFDI Lab\Dekstop is the location from where I embedded the hello.exe into the document.

\AppData\Local\Temp – That’s the location where MS Edge extracted a working copy of the embedded object when I double-clicked on the SusDoc.pdf

This is good to know because \Temp folder is a huge tattle-tale, and will contain traces of whatever Edge (and other viewers) opens. It’s not the best source of artifacts, but it’s potentially a viable one, especially if you catch it “fresh”, before it’s overwritten.

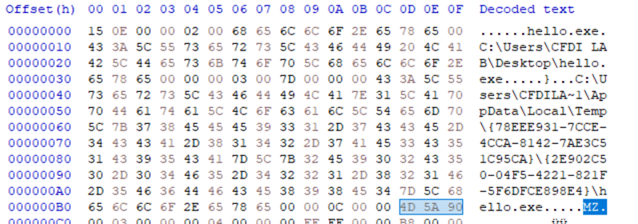

Scrolling lower, I reach a vital clue – it’s an executable file named hello.exe. It even has the ASCII “MZ” file signature header (in hex, it would translate to 4D 5A, as mentioned earlier).

So, if I was analyzing this without knowing what the contents are, I now have 3 red flags: an obfuscated document with an embedded object that is an executable program.

Digging deeper. What’s the rest of the noise and why is my object 15 KB uncompressed, compared to a 3 KB payload?

Because OLE doesn’t store the file by itself.

An embedded object is packaged inside an OLE Compound File is the old Microsoft mini-filesystem format. That structure includes multiple streams (metadata, descriptors, directory entries, and the actual payload) wrapped around the file I inserted. Even tiny payloads expand significantly once they’re placed into an OLE container. Let’s see if I can carve out my original hello.exe from this pile.

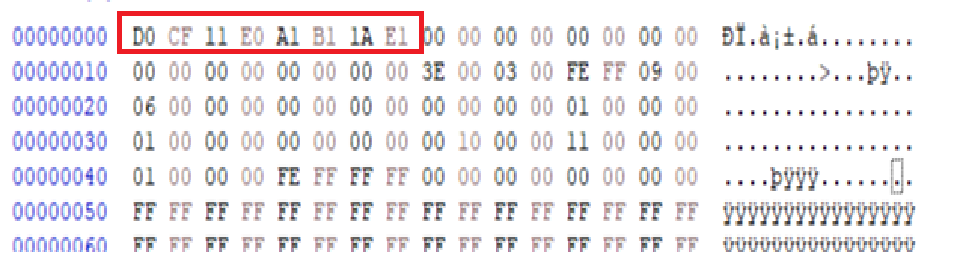

5) Open oleObject1.bin in HxD

So, based on the D0 CF 11 E0 A1 B1 1A E1 file signature, I know that it’s an OLE Compound File which is the type of OLE Object that is frequently abused by the bad actors. One step slower to my payload!

6) Search > Fine > hex-value “4D 5A”

More than half way through the whole file, there it is, my MZ 4D 5A executable payload. Theoretically I should be able to carve this out and just have my clean “sample”.

Before I do that, let’s look at the totality of the oleObject1.bin, because that’s just another compressed container. Rename to .zip, open the archive.

It’s a matreyoshka doll file of other files! My executable is in the [1]Ole10Native sub-file. The size is 3.609 KB, which is much closer to the original executable’s size. At this point I was on the mission to get my exact file extracted from this document.

6) Open in Notepad: Yep, it has some metadata of my original “hello.exe” plus more random stuff that wasn’t in my original program. Open the Ole10Native in HxD:

So, it’s not exactly my executable – you can tell because it starts with a bunch of added stuff when it was packed as an object into the document. Let’s see if we can make it work?

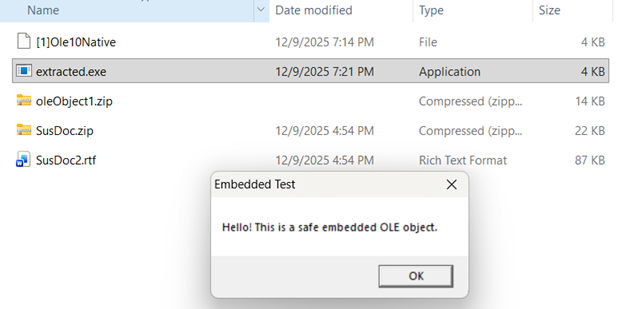

7) Delete everything before 4D 5A. File > Save as “extracted.exe” Run it. The newly extracted exe does exactly what I created it to do, which is popup a window with a button to close it:

So at least I can tell it seemingly does what it supposed to do, but is it the SAME? Only one way to tell, and that’s by verifying the has of the original file that I created.

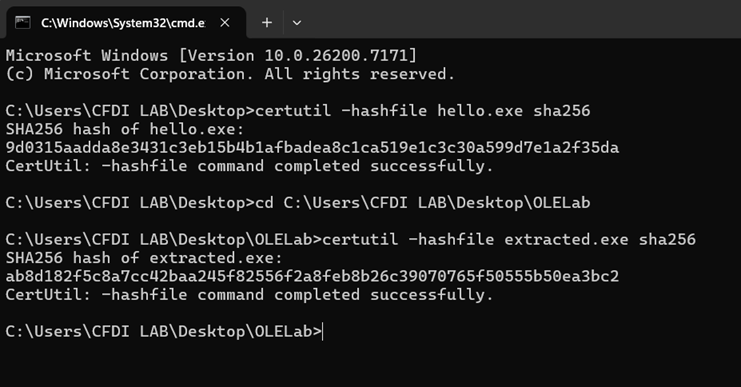

Use Certutil -hashfile command, or any hash generator/comparison tool.

The hashes don’t match, which I knew it wouldn’t. When I compared the original hello.exe and extracted.exe in HxD, I saw that the extracted file did not end on the same offset as my original file did. If I cheat and just strip away the extracted.exe’s trailer metadata to match my original – the hashes match. But that’s not a viable solution.

So while it was acting as my original exe and didn’t throw any errors, bit-by-bit it’s not the same file. That’s important. Just because something acts and looks as the original, always verify that the hash! In a real file analysis, if the hash doesn’t match – you didn’t extract the correct file. This also means that if you are trying to match it to a sample of a known file/malware – you won’t get any hits. If I was carving a completely unknown file, how do I know I didn’t leave out a crucial detail?

Why didn’t they match? OLE Object will usually have a bunch of trailer metadata and I saw that in the HxD. What now? Actual file carving. There are tools that can do this for me, but I’d like to be able to do it manually. Some file types will ave defined trailers, which I can use to guide me. Some file types don’t, and I have to figure out where they end by looking at the “offset map”. The size of the content and the padding after it can be found in the PE header. This is a task for another Lab.

- Review:

1) I looked at a suspicious .pdf file, identified the real file type by looking at the magic byte, and identified it to be a .docx file

2) I looked at the raw data of the file and saw that it had some sort of an embedded object inside

3) I learned the structured of .docx files and how to look inside of one to see the contents, as well as other information that can contain useful artifacts.

3) I extracted the object and identified it as a, executable file (a definite red flag!)

4) I “extracted” the executable file for further analysis, verified the hashes against the original file to verify is they are the same

5) I determined that they were not the same files, even though the extracted program behaved as the original.

6) I learned that OLE packaging adds additional metadata to the file so I would need to carve the file outside of that noise.

7) There are tools that can be used for data carving, but knowing how to do it manually is very useful. This will be in the later labs.